Inflation isn’t going to hurt the bankrolls of sports team owners.

In fact, it may help.

While the uber-rich will have to pay a little more for their eggs at the grocery store – just like everyone else – inflation isn’t likely to affect the bottom lines at their sports properties.

“I’m resting pretty easy if I’m an owner,” said Tim Clarke, a senior analyst at PitchBook, which researches private financial markets. “That’s how people are viewing assets of the professional sports industry. They’re just not going down.”

Inflation surged this year to levels unseen for four decades, slowing the economy and raising prices for consumers from the checkout line to the gas pump. For the most part, sports are no exception: Rising costs are making it more expensive for fans to go to games, for families who participate in youth sports and for college athletic departments trying to stay on budget.

But the millionaires and billionaires who own sports team won’t be feeling the pinch, whether it’s the day-to-day cost of running the business or the sale price when they decide to move on. On the contrary: A franchise can be a safe place to park money and ride out a bear market.

PHOTOS: Inflation or not, price of pro sports teams keeps going up

“I do think there is somewhat of a hedge,” said Inner Circle Sports CEO Rob Tillis, who has worked on the sale of dozens of teams in all four major U.S. pro sports and the top international leagues. “I have been doing this for 30 years. We’ve been through lots of business cycles and valuations have been strong. I don’t see that as any different now.”

Most sports owners are also well-capitalized enough to keep their team budgets separate from their outside business and other sources of wealth. So even though rising interest rates have cooled the housing market, that’s unlikely to affect Cleveland Cavaliers and Rocket Mortgage owner Dan Gilbert, who with an estimated net worth of almost $52 billion is the 23rd-richest man in the world, according to Forbes magazine.

(One exception: Losses in the Bernard Madoff Ponzi scheme squeezed the Mets payroll and forced owner Fred Wilpon to sell off first part, then the rest of the team.)

“These guys, they have so much money that I think if they start to get pinched elsewhere, it’s more or less a rounding error for their clubs,” said Tom Pitts, the European head of LionRock Capital, a private equity firm that has a one-third interest in the Inter Milan soccer team. “Most of these guys haven’t stretched to buy the club. It’s an expensive hobby.”

Rising interest rates could make it more expensive for would-be owners to buy into the club if they have to borrow money to pay for their new prize. “It just costs a lot more money in absolute dollars to service the debt,” Pitts said.

A handful of high-profile teams are currently on the market.

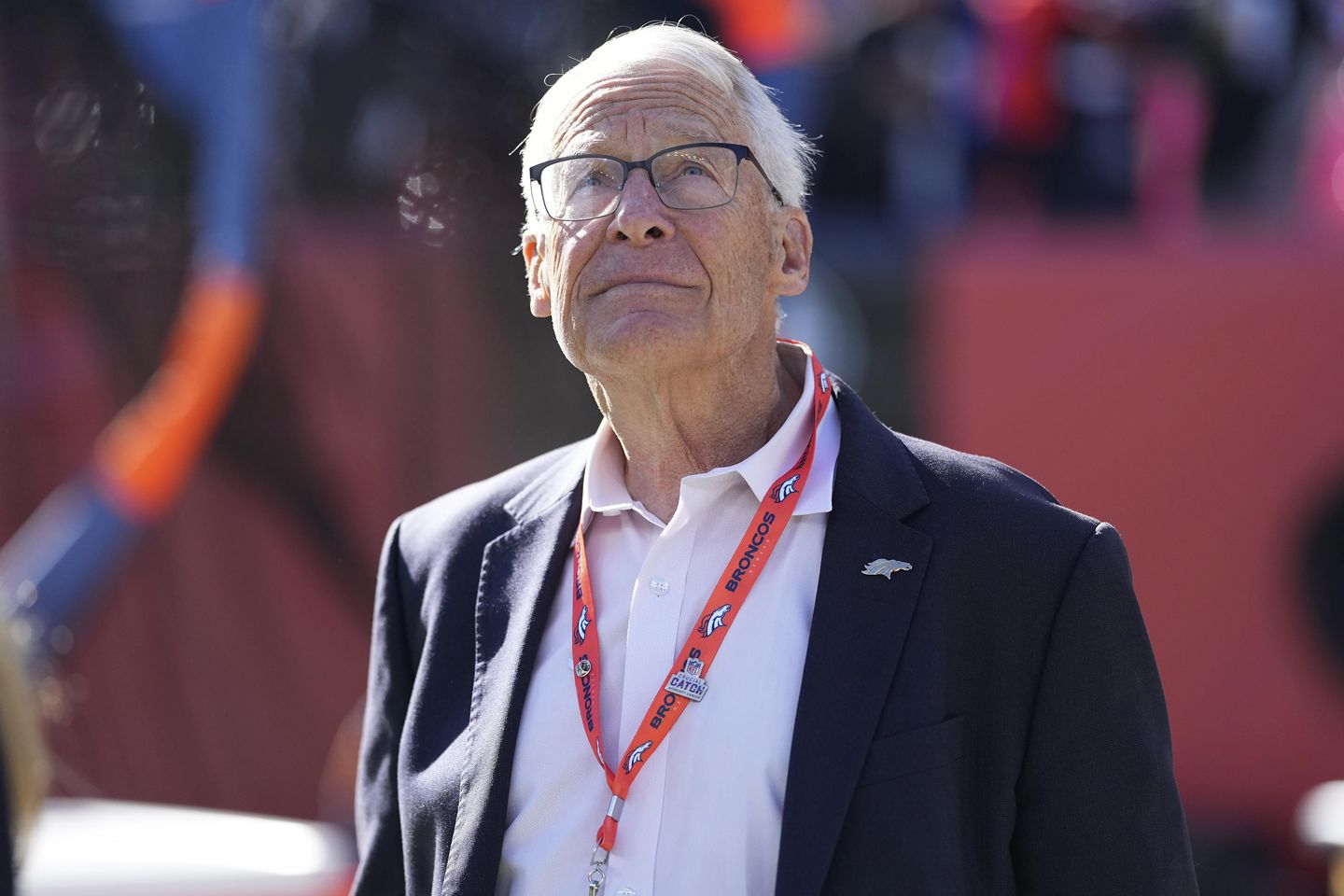

Washington Commanders owner Dan Snyder, who is under pressure to sell his team after an investigation revealed a toxic corporate culture, says he would consider unloading all or part of the once-proud NFL franchise. It is expected to fetch even more than the $4.65 billion paid for the Denver Broncos this summer by Walmart heir Rob Walton, who with an estimated net worth of $61 billion is the 16th-richest person in the world.

Robert Sarver has put his teams, the NBA’s Phoenix Suns and the WNBA’s Phoenix Mercury, on the market after an investigation found evidence of a racially and sexually insensitive workplace. Baseball’s Washington Nationals are for sale and the family that owns the Baltimore Orioles has made noise about selling, as well. The NHL’s Ottawa Senators can also be had for the right price.

Two of English soccer’s biggest names, Manchester United and Liverpool, are also on the market. Man U. was valued by Forbes in September at $4.6 billion – just a bit higher than Liverpool; both are expected to eclipse the $3.2 billion price paid for Chelsea this spring that was briefly the highest ever for a sports team.

That record was less than two weeks old when the Broncos deal was announced.

“You’ve got the likes of the Waltons, and it’s a drop in the bucket,” Clarke said. “It’s a club. It’s like, ‘When is the next Picasso up for sale?’ … The value sector has nothing to do with the economy. There’s always demand and there’s always scarce supply.”